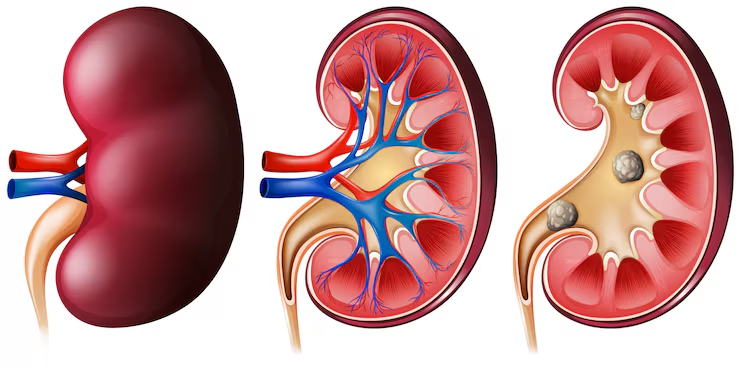

Scientists are approaching a significant milestone in organ transplantation through the development of what they call a “Universal Kidney.” In a collaborative effort between Canadian and Chinese researchers, a kidney was successfully modified to be theoretically compatible with all blood types and was shown to function briefly in a brain-dead human recipient.

The innovation centers on transforming a type A kidney into a type O variant — effectively removing the blood-type-specific antigens that typically trigger immune rejection. To achieve this, the researchers used specialized enzymes to strip away the sugar molecules responsible for the organ’s blood type identity. By eliminating these markers, the kidney was temporarily rendered “invisible” to the immune system. Biochemist Stephen Withers of the University of British Columbia likened the process to “removing the red paint from a car and revealing the neutral primer beneath,” illustrating how the immune system can no longer recognize the organ as foreign once its surface identifiers are gone.

However, despite this initial success, the procedure’s stability remains a major concern. Within three days, the type A antigens began to reappear on the kidney’s surface, triggering a mild immune response. Although the reaction was less severe than expected and the body appeared to begin adapting, the partial return of antigens highlights a crucial limitation: the modification’s temporary nature. For human clinical trials to proceed, the antigen-free state must be maintained over a much longer period.

The study, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, also leaves several important questions unresolved. For instance, it is unclear whether the enzymes used to strip the antigens might have unintended side effects or long-term toxicity. Additionally, while the research focuses on blood-group antigens, other immune mechanisms — such as T-cell responses and non-blood-type antigens — could still cause rejection.

If these technical challenges can be overcome, the implications would be transformative. A truly universal donor kidney could drastically reduce transplant waiting times, alleviate organ shortages, and make allocation systems fairer by removing blood-type compatibility barriers. Yet, as the reappearance of antigens demonstrates, the path from laboratory proof-of-concept to clinical application remains complex.

In summary, while the study represents a bold and promising step toward universal organ transplantation, its limitations underscore the need for further biochemical refinement and comprehensive immunological testing. The promise is real — but so are the hurdles.