Space agencies and defense researchers are moving closer to testing nuclear-powered rocket engines, reviving interest in nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP) as a potential tool for deep-space exploration. Although no such engine is expected to fly this year, plans are in place for the first in-space demonstration of an NTP system in early 2026. A successful test could pave the way for operational nuclear-powered missions later in the decade and into the 2030s.

NTP is frequently cited as a technology that could significantly shorten travel times and expand mission capabilities, particularly for crewed and robotic missions to Mars. However, its development also raises longstanding concerns related to safety, radiation exposure, and the handling and potential spread of nuclear materials both in space and on Earth. As progress accelerates, proponents and critics alike are calling for a clearer assessment of both the benefits and the risks.

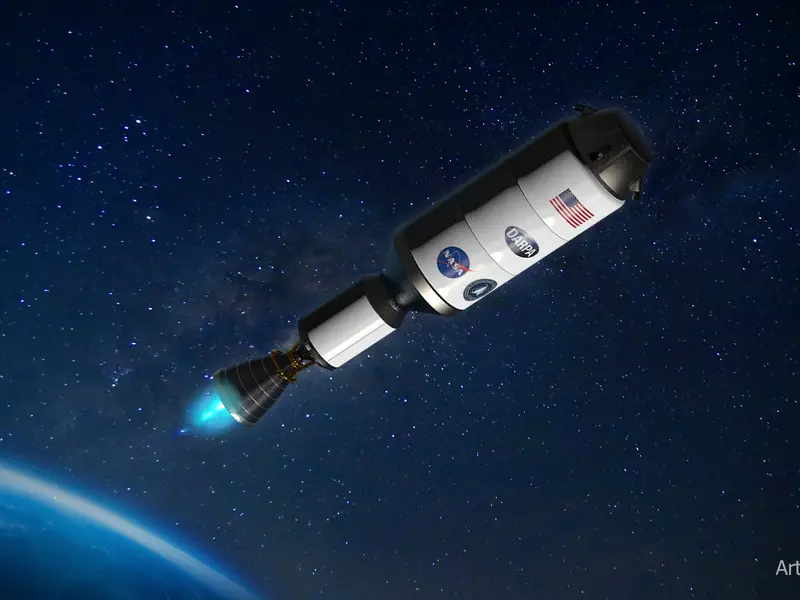

Unlike conventional chemical rockets, which rely on combustion between fuel and an oxidizer, nuclear thermal propulsion generates thrust using heat produced by nuclear fission. In an NTP engine, liquid hydrogen is passed through a compact nuclear reactor integrated into the propulsion system. As uranium fuel undergoes fission inside the reactor, it produces intense heat, rapidly raising the temperature of the hydrogen. The superheated hydrogen is then expelled through a nozzle to create thrust.

This approach offers a substantial efficiency advantage. Nuclear thermal engines are expected to achieve roughly twice the efficiency of the most advanced chemical rockets currently in operation. Higher efficiency allows spacecraft to travel greater distances using less propellant or to carry heavier payloads without increasing fuel requirements. Hydrogen’s low molecular mass further enhances performance, as it can be accelerated more easily than the heavier exhaust products typical of chemical propulsion.

Under current concepts, nuclear thermal engines would not be used for launches from Earth’s surface. Instead, spacecraft would first be placed into orbit using conventional chemical launch vehicles. The nuclear engine would only be activated once the spacecraft is already in space, a strategy intended to limit the risks associated with launching nuclear material from the ground.

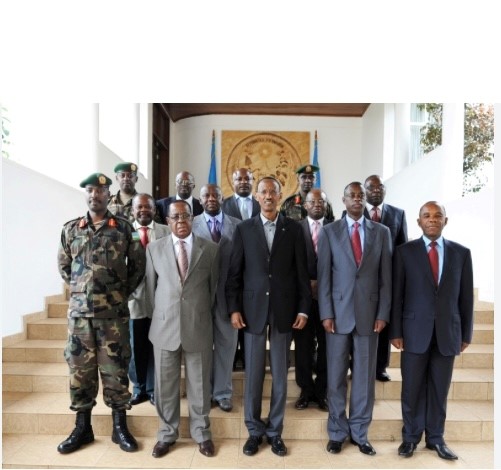

The most advanced NTP initiative is a joint effort by NASA and the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Known as DRACO—short for Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations—the program aims to conduct the first in-space test of a nuclear thermal rocket. The demonstration is currently scheduled for early 2026, though delays could push the test into 2027. Lockheed Martin is leading development of the spacecraft, while BWX Technologies is responsible for producing the nuclear reactor and fuel.

If the demonstration proceeds as planned, it would mark a significant milestone in space propulsion, potentially reshaping how future deep-space missions are designed while intensifying debate over the role of nuclear technology beyond Earth.